During a successful trade mission to Australia last week, one of our Fijian-grown crops garnered plenty of attention at the Sydney Fine Food Show – breadfruit. Root crop exporter, Farmboy, had taken a few packs of frozen breadfruit to test the market and to our joyful surprise discovered this common, yet often underutilized fruit, was largely unknown to the Australian audience at the show. Pan fried and simmered in a classic Fijian curry sauce, our humble breadfruit surprised many and opened both our eyes to its great export potential. Our exporters have previously only thought of expatriate Fijians living overseas as their market, but exotic produce like breadfruit has the potential to find its way on to the tables of the world’s top restaurants for everyone to enjoy. It’s bread-like pillowy texture and subtle sweetness is mostly unknown overseas, making breadfruit an exotic and premium export commodity. At Malamala Beach Club, French fries are replaced by island fries that include breadfruit. Although Fiji exports the more common dalo (taro) and cassava around the world, breadfruit is an untapped goldmine for our farmers, especially because its origins are uniquely South Pacific. If the world loves our pristine artesian water, wait until it discovers the nutritional powerhouse and culinary delights of breadfruit.

From PNG WITH LOVE

Unlike coconuts, which can float across vast oceans and wash up on beaches to germinate, breadfruit seeds and seedlings spread across the world by boat – specifically by the same seafaring explorers who discovered and settled the Pacific islands. Botanical researchers can trace its origins to Melanesian Papua New Guinea, and was taken across the South Pacific, Malay Archipelago, Hawaii and quite possibly South America by early Polynesian settlers thousands of years ago. Breadfruit was introduced as one of the many “canoe plants” the Polynesian explorers travelled with as they explored and conquered the islands, which also included yaqona (kava), according to Hawaiian voyaging traditions. Known as ulu or uto in the region, the secrets of this revered sweet starch remained in the Pacific Islands until European explorers discovered it.

British want breadfruit for slaves

In 1769, Sir Joseph Banks sailed with Captain James Cook to Tahiti, and discovered the delights of breadfruit. The colonialists recognised breadfruit as a readily available and high-energy source of food that could cost effectively feed its enslaved labourers across the colonies — a slave food. They proposed to King George III that a special expedition be commissioned to transport breadfruit plants from Tahiti to the Caribbean. In 1787, the infamous William Bligh was appointed Captain of the HMS Bounty and was instructed by the Royal Crown to transport over 1,000 breadfruit trees from Tahiti to the Caribbean. However, a month into that voyage, Bligh’s crew mutinied-expelling him from the ship in a longboat and throwing all the breadfruit plants overboard. Bligh successfully navigated the small boat on a daring 47-day voyage to Timor without charts or a compass. The ambitious Captain eventually returned to Britain, and five years after the original voyage, commissioned a second trip aboard the HMS Providence to bring breadfruit to the colonies.

Breadfruit spreads across the globe

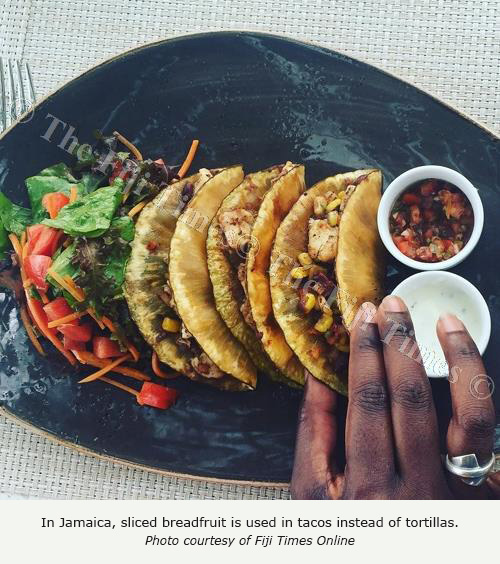

It was this journey that successfully introduced breadfruit to the West Indies. There you can find some of the original trees, planted over 200 years ago in Jamaica, still producing fruit, with breadfruit an integral part of the Jamaican diet today. Today, hundreds of varieties of breadfruit can be found in nearly 90 countries from the Pacific Islands, to Southeast Asia to the Caribbean and Central America. Left untouched, a tree can grow to near 25 metres, and yield between 150-200 fruits each year. One hundred grams of fruit has 27 grams of carbohydrates, 70 grams of water, as well as vitamins, potassium, calcium, magnesium, and other minerals. While the easily grown trees, with its distinctive large, cut leaves, flourished in the South Pacific, it took more than 40 years for the breadfruit to become popular in the Caribbean. Now, every Jamaican household has at least one tree in its back yard and breadfruit, or breshay as its known, is a staple diet eaten at breakfast, lunch, dinner, and even as a snack. It is baked, fried, boiled, roasted and even turned into a juice.

Mythical ulu legend in Hawai’i

Some years ago I was fortunate to learn the legends and history of the Polynesian Hawaiians, directly from their descendants on a special trip to Hawai’i including the canoe plants. When breadfruit was first cultivated in Hawai’i more than 1700 years ago, it was revered like the “Tree of Life” coconut tree. The trunk was used to make surf boards, drums, canoe parts, poi boards and wood for house and furniture construction. The inner bark of the breadfruit tree lent itself as a second-grade tapa cloth whilst its leaves were used like fine sandpaper to polish utensils, bowls, or nuts used in their garland leis.

Breadfruit was also known as a natural medicine. The young flower buds were used as a preventative medicine for mouth and throat disease. The white sticky sap, that oozes from the ripened breadfruit became glue, caulking, chewing gum, and an early medicine plaster for cuts. And of course breadfruit filled the stomach of many Hawaiian. The legendary origin of the breadfruit tree contributed to the legend of their war-god Kuka’ilimoku. During a time of famine, he buried himself in the ground, only to reemerge again as a healthy breadfruit tree.

“Eat some, feed our kids,” he told his mortal wife and subsequently saved his family from starvation. There is a saying in Hawai’i: “Look for the oozing breadfruit and do what the war god’s wife did; marry someone who always makes sure you have breadfruit.”

Fiji’s ancient history has much connection to the legends of the Polynesian explorers and the origins of the Melanesian breadfruit. This exotic fruit is so much more than just another food source that Fiji could export, it is an enduring reminder and legacy of one of humankind’s greatest seafaring civilizations, whose culinary appreciation and rediscovery has only just begun.

Source: Fiji Times Online