Known internationally as “snake fruit”, the exotic salak derives its name from its reddish-brown scaly skin. While the fruit looks intimidating to eat, peeling the skin reveals a white clove-like flesh. Gourmands describe the fruit as crunchy like an apple but tastes like a mix of pear, pineapple, and banana with hints of jasmine and lily. While it is grown mostly for food, recent studies reveal that salak has antioxidant properties.

Salak (Salacca zalacca) is native and widely cultivated in Java and Sumatra, Indonesia and there are a few growers in Thailand, Vietnam, and Malaysia. It has been introduced to New Guinea; the Philippines; Queensland, Australia; Ponape Island, Caroline Archipelago; and the Fiji Islands.

Plant Description

The fruit grows from a very short-stemmed palm tree, with leaves up to 6 m long. Leaves resemble those of coconut trees with a 2 m-long petiole, laden with spines up to 15 cm long and numerous leaflets. Fruits are usually produced when the trunk reaches 10 to 20 cm. Roots are adventitious and grow superficially that strong winds can topple tall trees.

Salak thrives in humid tropical lowlands and soil pH between 5-7. Because of the superficial root system, the palm requires lots of water all year round but cannot stand flooding. Fruit yield and quality in Java diminish on plants above 500 m altitude. Salak is usually grown under shade.

Fruit Description

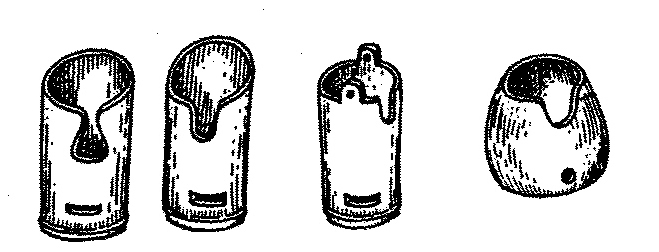

The fruit grows in clusters at the base of the palm. They have the same size and shape of a ripe fig. It can be peeled by pinching the tip, causing the skin to unravel and it can easily be pulled off. Salak contains three garlic clove-shaped lobes, each having a large inedible seed.

Varieties

There are at least 30 Salak cultivars grown throughout Indonesia. Two popular cultivars are Salak Pondoh from Yogyakarta province and Salak Bali from Bali Island.

Salak Pondoh is popular among Indonesian consumers because of the intensity of its aroma, which can seem overripe even before full maturation. It has three superior variations: Pondoh Super, Black Pondoh, and Pondoh Gading. Market price of this variety is around Rp 10,000-12,000 (USD 1.10-1.30) per kg.

On the other hand, Salak Bali is a popular with both locals and tourists because of its lighter aroma. It feels starchy when eaten. The most expensive cultivar of the Salak Bali is the Gula Pasir, which literally means “sand sugar” because of its fine-grained properties. Gula Pasir is smaller than the normal salak but notably sweeter. It fetches for Rp 15,000-30,000 (USD 1.50-3.00) per kg in Bali markets.

Propagation

Seeds can be sown directly in the field or in nursery beds, however, seed propagation is not recommended as fruit quality and yield are inconsistent.

Vegetative propagation is more commonly used to maintain yield and quality. The most common methods is through plant suckers. However roots are often intricately entangled and utmost care is necessary to prevent damage.

Indonesian farmers carefully dig around the roots and plant the suckers in segmented bamboo tubes or coconut shells, while the suckers are still attached from the plant. The plants are then later removed to be planted in the field.

Culture

Young palms require heavy shade and is normally intercropped in mixed gardens with bananas, mangoes, etc. Male trees should be around 10% of the total population and are evenly dispersed among female trees. Hand pollination is practiced by shaking a flowering male spike above a female flower.

Weeding should be done before the leaf canopy is closes. Suckers have to be removed because they can reduce the fruit yield of the mother palm. Lateral shoots may be spared and be allowed to grow into fruiting stems.

Old plant parts are cut off and either buried or burned for fertilizer. Farmers also use manure, urea, triple superphosphate, and potassium muriate. Different fertilizers have various effects on the fruit – using nothing but urea is said to produce large but perishable fruits.

Pests and Diseases

Common diseases include fruit rot caused by Mycena sp., black leaf spots caused by Pestalotia sp., and pink disease caused by Corticium salmonicolor. Pests include weevils (Omotemnus miniatocrinitus, O. serrirostris, and Nodocnemis sp.), Monophagous beetle (Calispa elegans), Polyphagous caterpillar (Ploneta diducta), leaf roller (Hidari sp.), scale insect (Ischnaspis longirostris) and several rodents. Farmers also report an unidentified grub feeding on the roots and devastating entire stands of salak orchards in central Java.

Harvesting

Salak fruits mature five to seven months after pollination. The tree produces fruits all year round but usually peak around May and December in Indonesia. Harvesting takes place at a fruit age of 5-7 months. Fruits are recommended to be harvested before they are fully ripe, by severing the bunch using a reaping knife.

In hot and humid climates, fruit will stay fresh in room temperature for a week after picking. Below 10oC, fruits last up to 3 weeks. Research is needed to establish maturity indices for harvesting and develop techniques to control fruit rot.

Market

Fruit quality is determined according to size, with bigger fruits fetching a higher price. For the domestic market, fruits are wrapped in banana leaves (or other cushioning systems) to prevent damage before they are packed in bamboos boxes. Bamboo boxes are recommended because they provide protection and air circulation. For export, fruits are arranged in single-layered cardboard carton.

Food Value

Salak is mostly consumed fresh. They can also be candied, pickled, canned and fermented into wine.

The fruit mostly contains carbohydrates, with trace amounts of sodium, potassium, calcium, manganese, iron, magnesium, zinc, and copper.

A study published in the Journal of Agriculture and Food Chemistry, rats fed with salak significantly hindered the rise in plasma lipids and the increase in antioxidant activity.

Other Uses

Boundary or barrier or support: A closely-planted row of palms forms an impregnable hedge and the very spiny leaves are also cut to construct fences.

The bark of the petioles may be used for matting. The leaflets are used for thatching.

References

- Hareunkit, R., et. al. “Comparative Study of Health Properties and Nutritional Value of Durian, Mangosteen, and Snake Fruit: Experiments In vitro and In vivo.” Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 13 June 2007. 10.1021.

- Herbs-Treat and Taste. “Snake Fruit Tree (Salak): Information and Benefits”. Herbs-Treat and Taste. 17 May 2011. <Retrieved from http://herbs-treatandtaste.blogspot.com/2011/05/snake-fruit-tree-salak-information-and.html on 17 August 2012>.

- Livestrong. “Snake Fruit”. Livestrong. 2 June 2007. <Retrieved from http://www.livestrong.com/thedailyplate/nutrition-calories/food/generic/snake-fruit/ on 17 August 2011>

- Salak Fruit Megalang. “Salak or Snake Fruit Production”. Salakpondohmerapi. 10 August 2011. <Retrieved from http://salakpondohmerapi.blogspot.com/2011/08/salak-or-snake-fruit-production.html on 17 August 2012>.

- Schuiling, D.L. & Mogea, J.P., “Salacca zalacca (Gaertner) Voss.” Plant Resources of South-East Asia. No. 2: Edible fruits and nuts. 1992. Prosea Foundation: Bogor, Indonesia.

- Sim, S. “A wondrous little ugly snake fruit”. Foodmanna. 22 September 2011. <Retrieved from http://foodmanna.blogspot.com/2011/09/wondrous-little-ugly-snake-fruit.html on 17 August 2011>.

- Supriyadi, et. al. “Maturity discrimination of snake fruit (Salacca edulis Reinw.) cv. Pondoh based on volatiles analysis using an electronic nose device equipped with a sensor array and fingerprint mass spectrometry”. Flavor and Fragrance Journal. 18 December 2003. Vol. 19. Issue 1.

- Wirajaya. “Salak Fruit Bali”. Bali Touring. <Retrieved from http://www.balitouring.com/bali_articles/balisalak.htm on 17 August 2012>.