by Lim Chia Ling, The Star Online

Visit any night market, fruit shop or supermarket and chances are you will find very few varieties of bananas being sold. For a crop that has been cultivated since ancient times in Malaysia (reputedly its place of origin), the lack of choice is surprising. A myriad of local species used to be available, but not anymore. A random check at two hypermarkets revealed only two choices: the imported Cavendish and the local pisang berangan.

The future scenario appears bleak for our local banana cultivars, which are not only up against foreign competition – in the form of the hardy and unblemished Cavendish – but also against other more profitable and productive crops. The problem is not just confined to bananas. Other fruits like pineapples and mangoes, too, suffer from dwindling varieties.

As farmers focus on growing only the best breeds for maximum yield, the challenge lies in the hands of the Malaysian Agricultural Research And Development Institute (Mardi) to stimulate research and conservation work to sustain diversity of these crops, and to ensure that a wealth of genetic resources exist for breeding quality and high-performing varieties.

Mardi director-general Datuk Dr Sharif Haron acknowledged Malaysia as a centre of diversity for wild and cultivated bananas.

“We’ve been collecting cultivated bananas since the 1980s, with over 200 accessions (each unique specimen group) currently conserved in our field gene banks in Serdang, Selangor, and Jerangau, Terengganu.

“There are about 27,500ha planted with bananas throughout Malaysia, with average productivity being 10 tonnes per hectare. That said, banana isn’t a staple fruit for us, and is often plagued by diseases like the Panama fungus and Moko bacteria that stunt productivity. It may not necessarily be a good thing to have too many varieties in the market too, as supply would be a problem. What matters more is high yield.”

Sharif says there are just two successful commercialised varieties so far. “Given the fact that there are a lot of banana germplasm in the country, there’s definitely potential for more varieties to be commercialised. Mardi is currently developing them for the local market, though not so much for international release.”

In Malaysia, banana varieties like berangan, mas, rastali and Cavendish are used in cookery while nipah, nangka, tanduk and pisang awak are used in desserts. These edible cultivars are derived from two wild species, Musa acuminata Colla and Musa balbisiana Colla. (The Musa acuminata is reportedly the most variable species and progenitor of cultivated bananas.)

Sharif says the commercial success of Cavendish, which dominates supermarket shelves, has a lot to do with promotion. For a fruit to do well, he says it has to meet consumers’ expectations and acceptance – the fruit must not just look good but taste good.

“The fruit’s features are as important as the quality, which means that for us to be competitive, we need to research and extract value-added properties like possible medicinal values. After that, we look into the yield, or how easy it is to plant and harvest, before domesticating it and planting it commercially.

“At Mardi’s research centre, we use technology to screen for genes responsible for certain elements or quality, as well as for pest- and disease-resistant traits. We also have a seed unit that produces high quality foundation seeds and planting materials for our research programmes.”

The production sites are located at Mardi stations in Serdang, Sintok (Kedah), Kuala Kangsar (Perak), Jerangau (Terengganu), Jelebu (Negri Sembilan), Kelang (Selangor) and Bintulu (Sarawak).

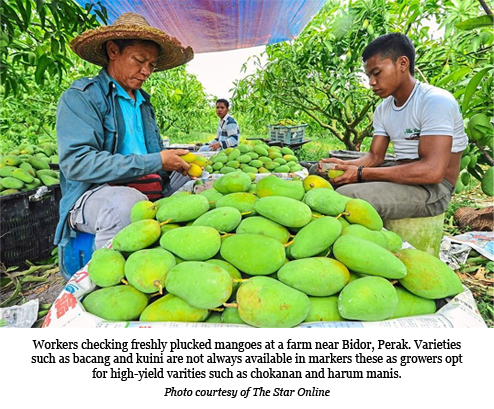

In the case of mangoes, the Department of Agriculture has registered 77 varieties and 209 clones to date, though only a few clones are popular for commercial planting – chokanan, harum manis, golek, maha and mas muda. The common mango, Mangifera indica, is the only widely cultivated species, though there are several other lesser-known species like the Mangifera odorata (kuini), Mangifera foetida (bacang) and Mangifera caesia (binjai).

An extensive 170 accessions of indigenous and exotic mango clones are kept as germplasm (seeds, tissue or plants, maintained for the purpose of breeding or preservation) in field gene banks in Mardi stations in Sintok, Jelebu and Serdang. Additionally, some 100 accessions of the kuini species and 40 of the bacang species are stored in Serdang. The best accessions have since been planted nationwide. Malaysia produces about 25,000 tonnes of mangoes from approximately 9,500ha of land; states like Perak, Perlis, Kedah, Malacca and Sarawak are noted as top growing mango regions.

With the pineapple, Sharif says Mardi has a few hybrid species ready for market release next year. Two cultivars are now in the market, the Josapine and Maspine.

“Most of our pineapple varieties are imported from the Philippines, with another two or three varieties from Sarawak. We have two main germplasm banks in Pontian and Kluang, Johor, for pineapple cultivation. The new varieties can only be released next year because it takes 15 months to ensure that there is sufficient planting materials (seedlings) for farmers to buy from us.”

Pineapples, too, are not spared from diseases, most notably the black rot that inflict the stems. This, Sharif says, underscores the importance of developing new varieties (through conventional breeding or semi-cloning) to increase crop resistance and survival.

Fruit security

A visit to Mardi’s expansive grounds in Serdang takes us through large tracts of field gene banks planted with various fruits and agricultural crops. The arboretum has hosted rare tropical fruits collected nationwide since the early 1980s. Meanwhile, its MyGenebank building houses laboratories and frozen rooms for long-term storage of seeds.

For Sharif, the importance of retaining diversity boils down to the objective of having a bigger gene pool. He says native species might not have the desired characteristics of high yield or pleasant taste, but they might have other valuable properties that can be leveraged upon when cross-bred for production of new varieties.

“The 200 accessions from 70 varieties of bananas in our collection (gene bank) is a fine example of some efforts we are taking to ensure those species don’t go extinct. While bananas are consumed fresh mostly by the global audience, Malaysians prefer fried bananas which require specific quality in the fruit. This is why certain genetic traits from indigenous species may be helpful in our research and development towards producing varieties that meet our needs,” he says.

Mardi is also collaborating with Biodiversity International, working with local communities on on-farm conservation of local fruits. Six conservation sites have been established, which also help to boost the income of local farmers. The sites are Yan and Bukit Gantang in Peninsular Malaysia, Sibuti and Serian in Sarawak, and Kota Belud and Papar in Sabah.

In Serian, rambutans and mangoes are cultivated in orchards as part of in-situ (natural habitat) conservation while ex-situ (out of natural habitat) conservation is done in the form of seed gene banks and germplasm collections.

Germplasm banks, though, are costly to maintain and require large spaces. Hence, technologies like in-vitro propagation and cryopreservation (in liquid nitrogen) may be key to conserving seeds that can survive when they are regenerated in future. However, some seed cannot survive freezing or drying, so they still have to be conserved as living collections in the field.

Mardi has allotted land in its various stations to conserve some 3,705 accessions, 168 species and 11,694 specimens of local fruits, with a special focus on under-utilised or rare fruits.

“It’s our role to expand on agrobiodiversity, which are key enablers for future crops. New varieties and crops are needed from time to time to complement the existing,” says Sharif.

“Ultimately, conservation requires a solid, consolidated effort so that we don’t waste resources, since labs are expensive to build. We have spent a lot on collecting, characterising, evaluating, conserving and documenting these fruits, as well as breeding and selecting them for market release.”

Source: The Star Online